Pelvic Floor Anatomy and Function: The Core of Pelvic Health

The pelvic floor refers to a dome-shaped group of muscles and connective tissues forming the base of the pelvis.

The pelvic floor stretches like a hammock from the pubic bone in front to the tailbone at the back, supporting the pelvic organs above it. In women, these organs include the bladder, uterus, and rectum; in men, the bladder, prostate, and rectum. The pelvic floor essentially acts as the body’s natural support sling, holding up these organs and keeping them in place.

Key Functions of the Pelvic Floor Muscles

Support of Pelvic Organs: The pelvic floor muscles provide constant support to the abdomino-pelvic viscera (organs like the bladder, uterus, and bowel). This supportive role is crucial – without a strong pelvic floor, organs can sag or press down on the vaginal walls in women or the rectal area in both sexes.

Maintaining Continence: A major function of the pelvic floor is to help control the release of urine and feces. The muscle fibers wrap around the urethra and rectum with a sphincter-like action that keeps us continent, meaning they stay contracted to prevent leakage. When we consciously relax these muscles, they allow urination or defecation to occur normally.

Resistance to Pressure Increases: The pelvic floor also braces against sudden increases in abdominal pressure. During activities such as coughing, sneezing, laughing, or lifting heavy objects, these muscles reflexively tighten to reinforce closure of the bladder and bowel openings. This prevents accidental leakage when pressure inside the abdomen rises (for instance, when you cough or strain).

Role in Core Stability and Posture: Along with the abdominal and back muscles and the diaphragm, the pelvic floor forms part of our “core.” It contributes to stabilizing the spine and pelvis. A well-functioning pelvic floor works together with your abs and diaphragm to maintain proper posture and support movements like standing, bending, and twisting.

Sexual Function: The pelvic floor muscles also play a role in sexual health. In women, a healthy pelvic floor contributes to vaginal tone and sensation. In men, the pelvic floor muscles support erectile function and ejaculation. Proper contraction and relaxation of these muscles are associated with sexual pleasure and orgasm for all genders. In fact, a strong pelvic floor can enhance sexual sensation, while dysfunction (such as overly tight or weak muscles) can lead to issues like pain during intercourse or erectile difficulties.

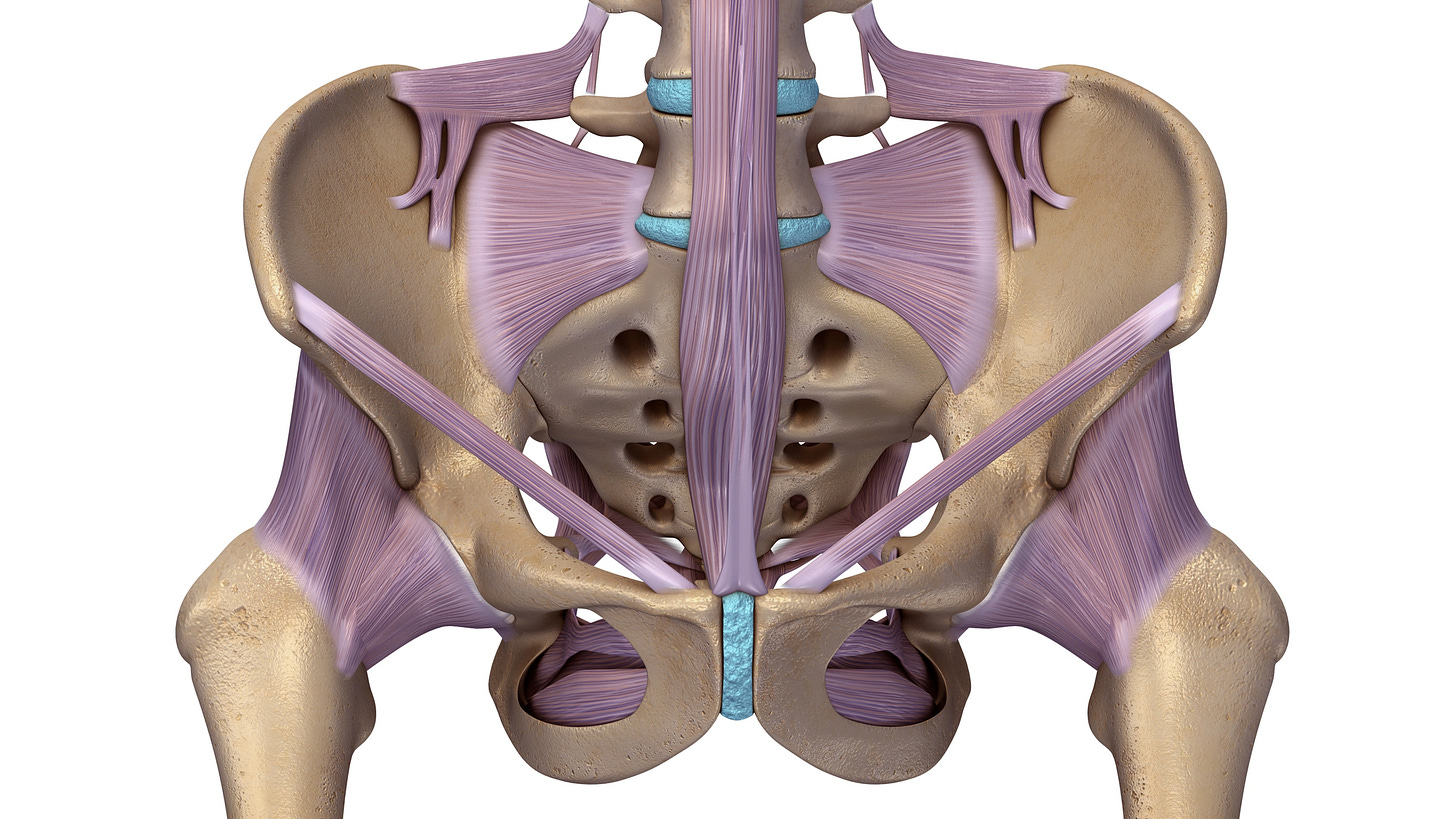

Structure of the Pelvic Floor

An easy way to visualize the pelvic floor is as a funnel or hammock at the bottom of the pelvic cavity. It has openings to allow passage of key structures. In females, there are three openings through the pelvic floor: the urethra (urine passage), the vagina, and the anus. In males, there are two openings: the urethra and anus. These openings pass through the pelvic floor muscles via small gaps called the urogenital hiatus (for the urethra and vagina) and the rectal hiatus (for the anal canal). Around each opening, the pelvic floor provides muscular support and can tighten as needed (for example, to hold urine in, the muscles around the urethra contract).

The levator ani is the largest and most important muscle group of the pelvic floor. It’s a broad muscle group (including the pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus muscles) that forms the bulk of the pelvic diaphragm. These muscles attach at the pelvic bones and meet in the middle to create a floor under the organs. The levator ani supports the pelvic organs from below and also pulls the rectum forward, helping maintain a bend (anorectal angle) that keeps stool in until you’re ready to go to the bathroom. Nearby is the coccygeus muscle, which completes the pelvic floor support toward the back (near the tailbone). Additionally, in the front part of the pelvic outlet, there is the urogenital diaphragm – a layer of muscle and connective tissue that supports the urethra and (in women) the vaginal opening.

Nerves and control: The pelvic floor muscles are under both voluntary and involuntary control. We can consciously squeeze them (like when doing Kegel exercises or trying to stop urine mid-flow), but they also reflexively contract during activities like coughing. Nerves from the lower spine (pudendal nerve and others from the sacral plexus) control these muscles. Damage to these nerves or muscles (for example, during childbirth or surgery) can weaken the pelvic floor and impair its function.

Why Pelvic Floor Health Matters

A healthy pelvic floor is essential for bladder and bowel control, organ support, and sexual well-being. When these muscles are working properly, you typically don’t notice them – they just do their job in the background. You stay dry when you sneeze, you can exercise without worrying about leaks, and your organs are held in their proper place. Strong pelvic floor muscles also contribute to a stable core, which can help prevent back pain and promote better posture.

On the other hand, if the pelvic floor muscles become weak or injured, people may develop problems such as urinary incontinence (leaking urine), fecal incontinence, or pelvic organ prolapse (when pelvic organs droop down). If the muscles are too tight or spasm (overactive pelvic floor), it can lead to issues like pelvic pain, painful intercourse, or difficulty emptying the bladder or bowels. We will explore these conditions in later sections, but it underscores how central the pelvic floor is to multiple aspects of health.

In summary, the pelvic floor is the unsung hero of the pelvis – a muscular foundation that supports organs, maintains continence, and enables healthy sexual function. Keeping these muscles healthy (through exercises and avoiding excessive strain) is important for everyone. In the following articles, we’ll delve into common pelvic floor problems and ways to prevent or manage them, but understanding the anatomy and function is the first step toward recognizing the value of pelvic floor health.